|

| 1 | +# How to Debug Performance Issues in Python |

| 2 | +#### Using Flamgraphs to get to the root of the problem |

| 3 | + |

| 4 | +I know from personal experience that debugging performance issues on Python servers can be incredibly hard. Usually, there was some event like increased traffic or a transient bug that causes end users to report that somethings wrong. |

| 5 | + |

| 6 | +More often than not, its _impossible_ to exactly replicate the conditions under which the bug occured and so I was stuck trying to figure out which part of our code/infrastructure is responsible for this performance issue on our server. |

| 7 | + |

| 8 | +This article explains how to use Flamegraphs to continuously monitor you code and show you exactly which lines are responsible for these performance issues. |

| 9 | + |

| 10 | +## Why You should care about CPU performance |

| 11 | +CPU performance is one of the main indicators used by pretty much every company that runs their software in the cloud (i.e. on AWS, Google Cloud, etc). |

| 12 | + |

| 13 | +In fact, Netflix performance architect, Brendan Gregg, mentioned that decreasing CPU usage even just 1% is seen as an enormous improvement because of the resource savings that occur at that scale. However, smaller companies also see similar benefits when improving performance, because regardless of size, CPU is often directly correlated with two very important facets of a software business: |

| 14 | +1. How much money you're spending on servers - The more CPU resources you need the more it costs to run servers |

| 15 | +2. End-user experience - The more load that is placed on your servers CPUs, the slower your website or server becomes |

| 16 | + |

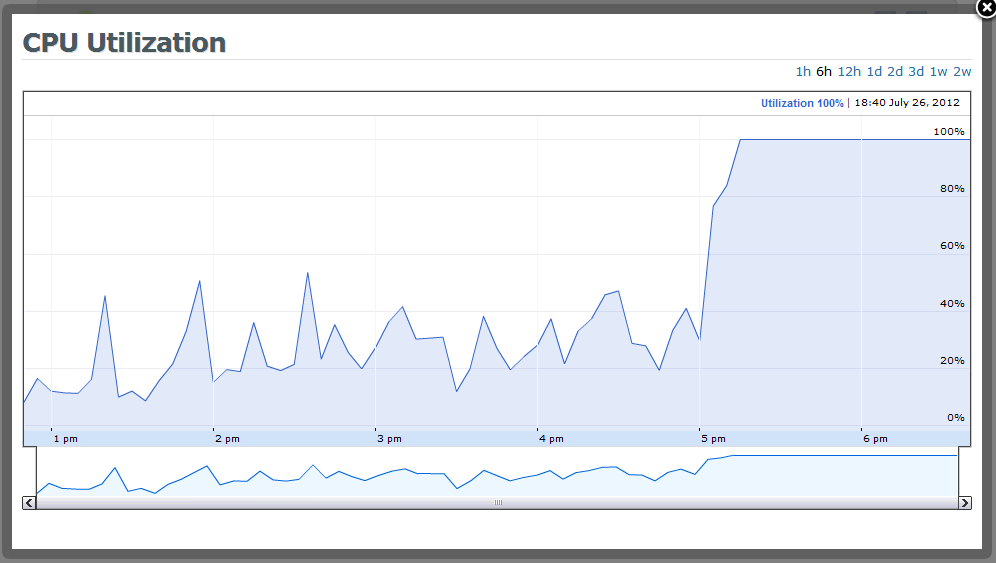

| 17 | +So, when you see a graph that looks like this, which is what you typically see in a tool like AWS that shows high-level metrics: |

| 18 | + |

| 19 | + |

| 20 | +You can, assume that during this period of 100% CPU utilization: |

| 21 | +- your end-users are likely having a diminished experience (i.e. App / Website is loading slow) |

| 22 | +- your server costs are going to increase because you need to provision new servers to handle the increased load |

| 23 | + |

| 24 | +But, the main problem is that you don't know _why_ these things or happening. **Which part of the code is responsible?** That's where Flamegraphs come in. |

| 25 | + |

| 26 | +## How to use Flame graphs to debug performance issues and save money |

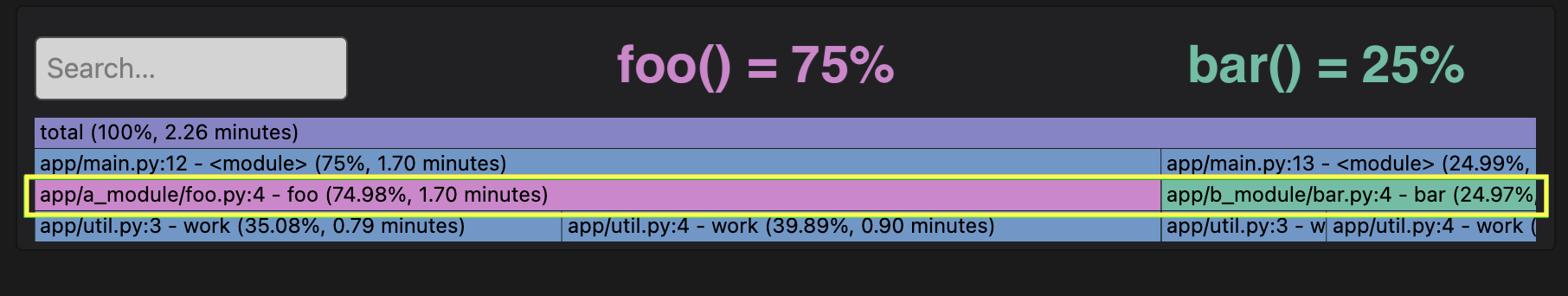

| 27 | +Let's say that this Flamegraph represents the timespan that corresponds with the "incident" where CPU usage spiked in the picture above. What that would indicate is that during this spike, you're servers CPUs were spending: |

| 28 | +- 75% of time in `foo()` |

| 29 | +- 25% of time in `bar()` |

| 30 | + |

| 31 | + |

| 32 | + |

| 33 | +You can think of a Flamegraph like a super detailed pie chart, where the biggest nodes are taking up most of the CPU resources. |

| 34 | +- The width represents 100% of the time range |

| 35 | +- Each node represents a function |

| 36 | +- Each node is called by the node above it |

| 37 | + |

| 38 | +In this case, `foo()` is taking up the bulk of the time (75%), so we can look at it improving `foo()` and the functions it calls in order to decrease our CPU usage (and $$). |

| 39 | + |

| 40 | +## Creating a Flamegraph and Table with Pyroscope |

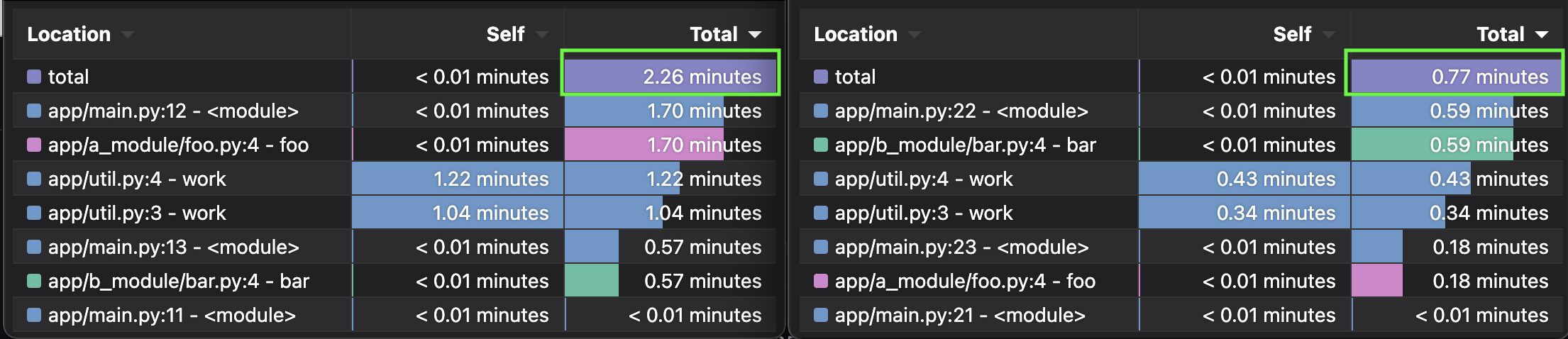

| 41 | +To create this example in actual code we'll use Pyroscope - an open-source continuous profiler that was built specifically for the use case of debugging performance issues. To simulate the server doing work, I've created a `work(duration)` function that simply simulates doing work for the duration passed in. This way, we can replicate `foo()` taking 75% of time and `bar()` taking 25% of the time by producing this flamegraph from the code beneath it. |

| 42 | + |

| 43 | + |

| 44 | + |

| 45 | + |

| 46 | +```python |

| 47 | +# where each iteration simulates CPU time |

| 48 | +def work(n): |

| 49 | + i = 0 |

| 50 | + while i < n: |

| 51 | + i += 1 |

| 52 | + |

| 53 | +# This would simulate a CPU running for 7.5 seconds |

| 54 | +def foo(): |

| 55 | + work(75000) |

| 56 | + |

| 57 | +# This would simulate a CPU running for 2.5 seconds |

| 58 | +def bar(): |

| 59 | + work(25000) |

| 60 | +``` |

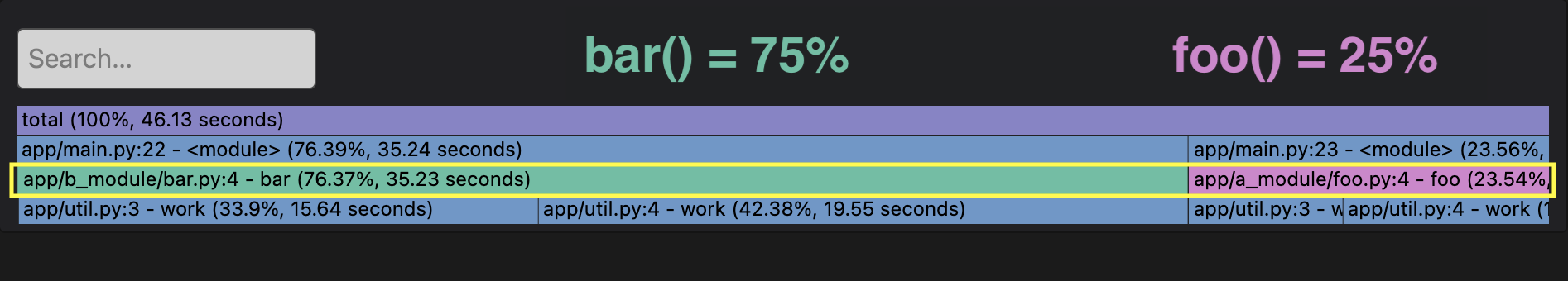

| 61 | +Then, let's say you optimize your code to decrease `foo()` time from 75000 to 8000, but left all other portions of the code the same. The new code and flamegraph would look like: |

| 62 | + |

| 63 | + |

| 64 | + |

| 65 | +```python |

| 66 | +# where each iteration simulates CPU time |

| 67 | +def work(n): |

| 68 | + i = 0 |

| 69 | + while i < n: |

| 70 | + i += 1 |

| 71 | + |

| 72 | +# This would simulate a CPU running for 0.8 seconds |

| 73 | +def a(): |

| 74 | + # work(75000) |

| 75 | + work(8000) |

| 76 | + |

| 77 | +# This would simulate a CPU running for 2.5 seconds |

| 78 | +def b(): |

| 79 | + work(25000) |

| 80 | +``` |

| 81 | + |

| 82 | +What this means is that your total cpu utilization decreased 66%. If you were paying $100,000 dollars for your servers, you could now manage the same load for $66,000. |

| 83 | + |

| 84 | + |

0 commit comments